In the fossil dinosaur boob, scientists find a hidden treasure

4 min read

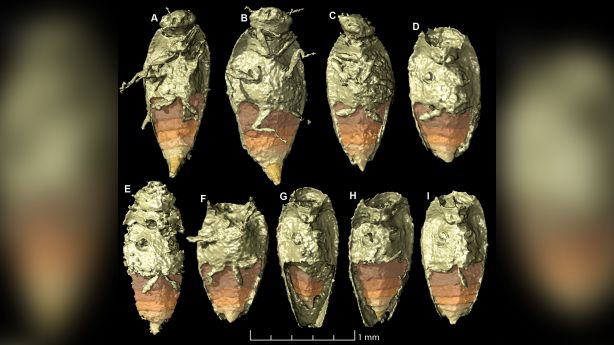

According to a study published Wednesday in the journal Current Biology, the small beetle Triamixa coprolitica is the first insect to be described from fossil feces. (Quarnstrom et al.)

Atlanta (CNN) – You might think fossil feces are just crap, but new research on a model has created a hidden treasure: 230 million years old, previously undiscovered beetle species.

Named Triamixa coprolitica, small beetles are found by fossil feces – or scanning method using the first insects and strong X-ray beams described from coprolites. A study Published Wednesday in the current issue of Biology. The scientific name also refers to the discovery of beetles in a cobrolite Triassic period, Which lasted from about 252 million to 201 million years ago, and is a subset of bugs called myxobaca – small aquatic or semi-algae beetles that feed on algae.

“These types of insect fossils are preserved in three dimensions, which are practically unheard of from the Triassic, so this discovery is very important,” said Sam Heads, director and chief supervisor at the university’s PRI Center for Paleontology. Illinois in Urbana-Champaign, via email. The heads were not involved in the study.

“I was amazed at how well the beetles were preserved, and when you modeled them on the screen, it was as if they were looking right at you,” said Martin Guernstrom, the study’s first author, an ancient researcher and postdoctoral fellow at the University of Uppsala, in Sweden. A statement. “This is facilitated by the calcium phosphate composition of the coprolites. This, along with the early mineralization of the bacteria, helped to preserve these delicate fossils.”

Calcium phosphate Important for bone formation and maintenance, and Mineralization When organic compounds are converted into inorganic compounds during decomposition processes.

Based on the size, shape, and other anatomical features of the fossil droplets analyzed in the previous research by the authors of the current study, the scientists expelled the cobrolites by the Sileserus opolencis, a small dinosaur about 6.6 feet long that weighed 33.1 pounds and lived in the Poland 230 million years ago.

According to one comment, “Silesarus had a flag at the tip of its jaws that could be rooted in debris and used to stab insects off the ground like modern birds.” News release.

“Although many individuals of Triamixa coprolitica appear to have been ingested by Silas, the beetle may be too small to be the only targeted prey,” Guernstrom said. “Instead, Triamixa shared its habitat with large beetles, which are characterized by fragmented remains and other prey in the cobrolites, which never ended up in the cobrolites in a recognizable form. Therefore, part of its diet contained insects.”

“There is not enough evidence at this time to say for sure whether these beetles are specifically selected by Silesarus,” Heads said.

“It may have been a common insecticide that could have caught an insect, and the beetles only escaped digestion because of their (very hard and strong outer skeletons,” the heads added. “Their small size certainly helped some of them stay that way because they were more likely to be swallowed whole and chewed whole. “

Another suggestion made by researchers is that, based on their findings, coprolites may be an alternative to another substance known to produce highly preserved insect fossils: amber, III, a hard, yellow and translucent fossil resin produced by extinct trees, which lasts About 66 million 2.6 million years ago.

“I have worked with amber preserved fossil insects for many years, and I agree with the authors that the level of protection found in coprolite specimens is very similar in both completeness and level of protection,” the leaders said. “It’s very significant.”

Since the oldest fossils from Amber are about 140 million years old, very old cobrolites could help make further progress into the past that researchers have not explored, the news release said.

“We do not know what insects looked like during the Triassic, and now we have the opportunity,” said Martin Fieke, associate professor of entomology at the National Sun Yat-sen University in Taiwan. “Perhaps, when many more cobrolites are analyzed, we will see that some groups of reptiles produce cobrolites that are not really useful, while others contain neatly preserved insect-rich cobrolites that we can read about. At least some idea.”

Researchers who detect coprolite insects can scan them in the same way that scientists scan amber insects, Ficke added, which will reveal minute details. “In that respect, our discovery is very promising, which basically tells people: ‘Hey, check more coprolites using micro CD, which has a good chance of finding pests, and if you find it, you can protect it well.’ “

The study team’s ultimate research goal, Guernstrom, is to “use coprolite data to reconstruct ancient food webs and see how they have changed over time.”

Related stories

Extra stories you like

“Communicator. Award-winning creator. Certified twitter geek. Music ninja. General web evangelist.”