The study of DNA illustrates two distinct prehistoric human groups

3 min read

Scientists have studied the oldest human DNA found in the British Isles so far and discovered two distinct groups that migrated to Britain at the end of the last Ice Age.

Published in Nature Ecology and Evolution, The new study from the UCL Institute of Archeology (University College London), the Natural History Museum and Francis Crick Institute researchers reveal for the first time that Britain’s recolonization consisted of at least two groups with distinct origins and cultures.

Researchers explored DNA evidence from an individual found at Gough Cave in Somerset and an individual found at Kendrick Cave in North Wales, which lived more than 13,500 years ago.

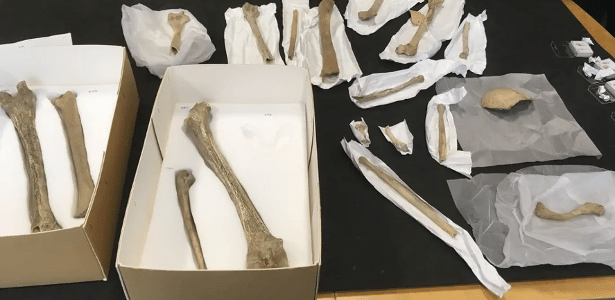

The study, which included radiocarbon dating and analysis as well as DNA extraction and sequencing, shows that it is possible to obtain useful genetic information from some of the oldest human skeletal materials in the country.

The authors say these genetic sequences now represent the oldest chapter in Britain’s genetic history, but ancient DNA and proteins promise to take us further in human history.

The researchers found that the DNA of a Gough Cave individual, who died about 15,000 years ago, indicates that his ancestors were part of an early migration to northwest Europe about 16,000 years ago.

However, the Kendrick Cave individual is from a later period, about 13,500 years ago, with its ancestors from a western hunter-gatherer group.

Scientists believe that the ancestors of this group originated from the Near East, migrating to Britain about 14,000 years ago.

“The finding of the ancestor so soon in Britain, only a thousand years away, reinforces the emerging picture of Paleolithic Europe, which is one of a changing and dynamic population,” wrote Mateja Hajdenjak of the Francis Crick Institute, a co-author on the study.

The authors note that these migrations occurred after the last Ice Age, when roughly two-thirds of Britain was covered by glaciers. As the climate warms and glaciers melt, drastic ecological and ecological changes have taken place and humans are beginning to return to Northern Europe.

“The period we were interested in, from 20 to 10,000 years ago, is part of the Paleolithic – the Paleolithic. This is an important period for the environment in Britain where there would have been significant climatic warming, an increase in forest area and changes in animal species available for hunting,” explains study co-author Sophie Charlton, who carried out the study while at the Natural History Museum.

Cultural differences

Also genetically, the two groups were considered culturally different, with differences in what they ate and how they buried their dead.

Chemical analyzes of the bones showed that Kendrick Cave individuals ate a lot of seafood and freshwater foods, including large marine mammals, said Rhiannon Stevens of the UCL Institute of Archeology.

On the other hand, humans in Gough Cave ate mainly terrestrial herbivores such as red deer, cows (including a species of wild cattle called aruchs) and horses.”

The researchers found that the two groups’ burial practices were also different. While animal bones were found in Kendrick Cave, it included portable art items such as a decorated horse’s jaw. No animal bones have been found that have shown evidence that humans have eaten, and scientists say this indicates that the cave was used as a burial site by its occupants.

In contrast, human and animal bones found in Gough Cave showed significant human modification, including modification of human skulls into “skulls,” which researchers believe is evidence of ritual cannibalism. Individuals from this earlier group appear to be the same people who created the Magdalen stone tools, a culture also known for its iconic rock art and bone artifacts.

“Musicaholic. Thinker. Extreme travel trailblazer. Communicator. Total creator. Twitter enthusiast.”