The man who served 17 years wrongfully imprisoned for the murder of his parents

6 min read

- Rafael Abuchaibe (@RafaelAbuchaibe)

- BBC News World

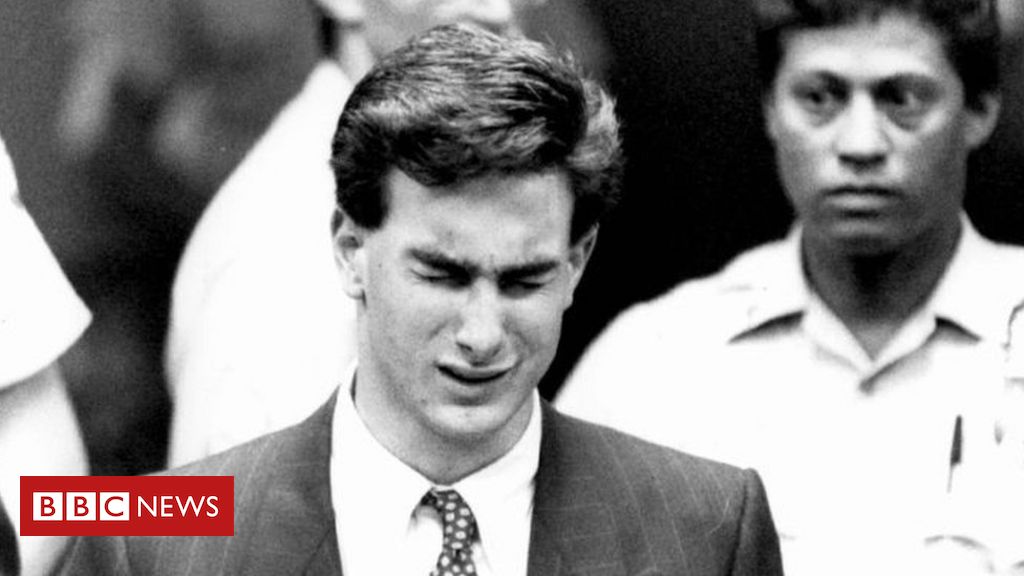

credit, Getty Images

Marty Tankliffe served 17 years in prison for killing his parents

In September 1988, on the first day of school, Marty Tankliffe, a 17-year-old American teenager, wakes up to find his mother dead and his father seriously injured in his office.

The young man did what any sane person would have done in this situation: He called the emergency services, which in the US are reached by dialing 911.

“[Eu estava] In complete panic, in shock. There is no way to describe the moment because what happened to me is something no one should have to go through.”

Marty never imagined that after that phone call he would become the prime suspect in his parents’ murder – and that he would spend 17 years in prison for a crime he didn’t commit.

Arrested in 1990 and released in 2007 – when the court reviewed his case and dismissed the charges – Marty Tankliffe tells his story, years after he regained his freedom and rebuilt part of his life.

happy childhood

Arlene and Seymour Tankliffe adopted Marty before he was born, and raised him in a suburb of Long Island, New York.

“My dad never grew older, but as I got older he was more financially stable, so I was given some of the things my dad or mom would have wanted when I was a kid,” he says.

Also, because Arlene and Seymour were more mature and financially stable, they were able to spend more time with Marty. They shared school and community trips and activities.

It is one of the many reasons Marty could not understand why on that fateful September morning, instead of taking him to the hospital or keeping him at home, the police took him to a brutal interrogation, of which there is no record.

“They saw me as a suspect from the start,” he says.

interrogation

Marty recalls that the interrogation began as expected, with questions in which the officers attempted to obtain details about the young man’s relationship to his parents or who he might have been a suspect.

Marty names Jerry Sturman – his father’s partner in the baking business – as the person he believes was behind the crime.

In a December 1988 lawsuit, representatives for Seymour Tankliffe alleged that Sturman owed Marty’s father nearly $900,000.

Steuerman was home playing poker with his parents and other guests until the wee hours of the morning.

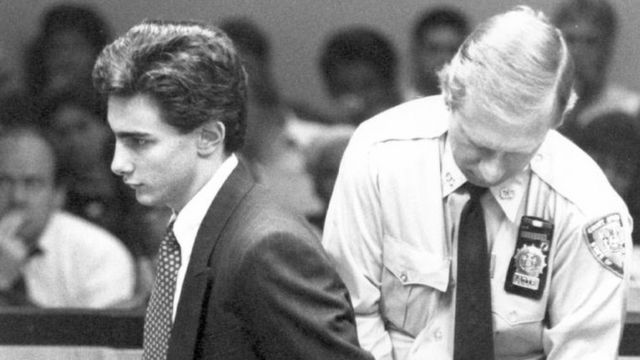

credit, Getty Images

As it turns out years later, Marty was considered a suspect from the start.

“But there was a turning point where the questions no longer had an investigative tone and became accusatory,” he says.

The principal investigator in the Tankliffe case was Detective James McCready, who died in 2015, and who discussed the case on several occasions with the press.

In an interview with US network CBS, McCready described one of the techniques he used during interrogation.

The interrogator said, “I went to an office, picked up the phone and called the extension closest to the interrogation room, and I got up and went to take my call. I pretended I was talking to another interrogator.”

McCready described to CBS that after putting off the fake call, he went into the interrogation room and lied to Marty, telling him that his father had been sobered up by adrenaline and that he had accused his son of being the shooter.

“In America, detectives can lie to suspects, and that’s what they did,” says Marty, telling the lies he’s heard.

“They said they found my hair in my mother’s hands, it’s not true. They said they pumped my dad with adrenaline, and he identified me as the one who attacked him, it’s not true.”

Police ruled Sturman out as a suspect when he turned up in California a week later, saying he fled out of fear of being charged with the murder.

credit, Getty Images

The jury found Marty Tankliffe guilty of killing his parents

As Marty explains, the detectives’ strategy in his case was based on “taking him down” just enough to get him to say what they wanted to hear.

This was evidenced by the trial, which began two years later in front of cameras.

One of the main pieces of evidence presented by the prosecution during the trial was a document written by Detective McCready but without Marty’s signature, which gave the weight of the confession.

Marty says he doesn’t remember exactly what he was going to say during the interrogation, but says he could have said anything.

“If you take a young suspect who has just been through something traumatic—and you isolate him, berate him, verbally abuse him—you make him believe there’s only one way out of that room, and that requires saying nothing.”

Sturman also served as a witness at the trial, saying he ran away in order to get life insurance that he could leave to his family, fearing he might end up in jail because Marty had declared him a suspect. “I didn’t do that,” Strowman said during the trial.

Marty was sentenced to two consecutive life sentences, with the possibility of parole after 25 years.

Marty says, “What I remember about that day is that they took me to the county jail and the clerk in the baggage room asked me, ‘What are you doing here?'” You cannot be guilty. “”

credit, Getty Images

Tankliffe devoted his time in prison to proving his innocence.

During his time in prison, Marty studied to become a lawyer so that he could contribute to his own defence.

In addition, he wrote to several retired prosecutors asking them to review his case.

14 years have passed.

freedom

In 2004, after years of collecting information, testimonies from nearly 20 witnesses, and new evidence, the defense requested a new trial.

Attorneys obtained at least 20 new testimonies – as well as physical evidence – that turned the sights on Seymour Tankliff’s partner.

One was the testimony of Glenn Harris, who claimed to have driven the car used by two of the gunmen, Joe Creedon and Peter Kent, to reach the Tankliffe house.

However, the appeal was denied.

In doing so, the defense shifted its focus to trying to move Marty’s case to another jurisdiction, because—as defense attorney Barry Pollack said—”there would be no justice for him in Suffolk County.”

It could take another three years for the Brooklyn appeals court to review the case and overturn Marty’s conviction because there was “not enough evidence” to find him guilty of the crime.

On that occasion, Marty says, it took him more than 24 hours to understand what was happening to him.

credit, Getty Images

In 2014, Marty Tankliffe graduated as a lawyer

“It wasn’t until the next day, when a guard brought me the paper and I saw my face on the front page, that I really realized what had happened. It was something I had worked on for a long time, and only understood when I saw it in print.”

When Marty was released, he had spent half his life at large and the other half behind bars. Because of this, he says the first steps he took after returning home were great.

“As we were leaving prison, I asked those who were with me to go slower, and when they asked me why, I told them this was my first step towards freedom and I wanted to take it slowly.”

The world changed between 1990 and 2007 – as did the lives of those around you. Marty graduated in Law after the age of 35 and had to adjust to a world dominated by technology.

credit, Getty Images

Marty married in 2014

“It’s hard to accept [o que aconteceu]This is one of the reasons why I became a lawyer. I am bitter because the system failed me and I am bitter because there were people who intentionally acted in a way that convinced me.”

“But as long as there are people who know the truth,” he says, “I feel good.”

“Devoted food specialist. General alcohol fanatic. Amateur explorer. Infuriatingly humble social media scholar. Analyst.”